Precambrian Plate Tectonics

How did continents move on early Earth?

I integrate geochronology with paleogeographic constraints obtained through paleomagnetic analysis to learn more about Precambrian plate tectonic processes.

Fortescue Group, Australia

I began my PhD research on the 2.7 Ga Fortescue Group in Pilbara, Western Australia; it’s thought to be an early example of a large igneous province. Previous research suggested that the Pilbara craton may have been moving rapidly during two different intervals of Fortescue Group deposition. I performed a detailed volcanostratigraphic study integrating paleomagnetism and geochronology across these intervals, with the goal of obtaining a rate of Archean plate motion. I produced 6 new paleomagnetic poles and 4 new U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS ages for the Fortescue Group that suggest far faster plate motion than observed today or for earlier in the history of the craton.

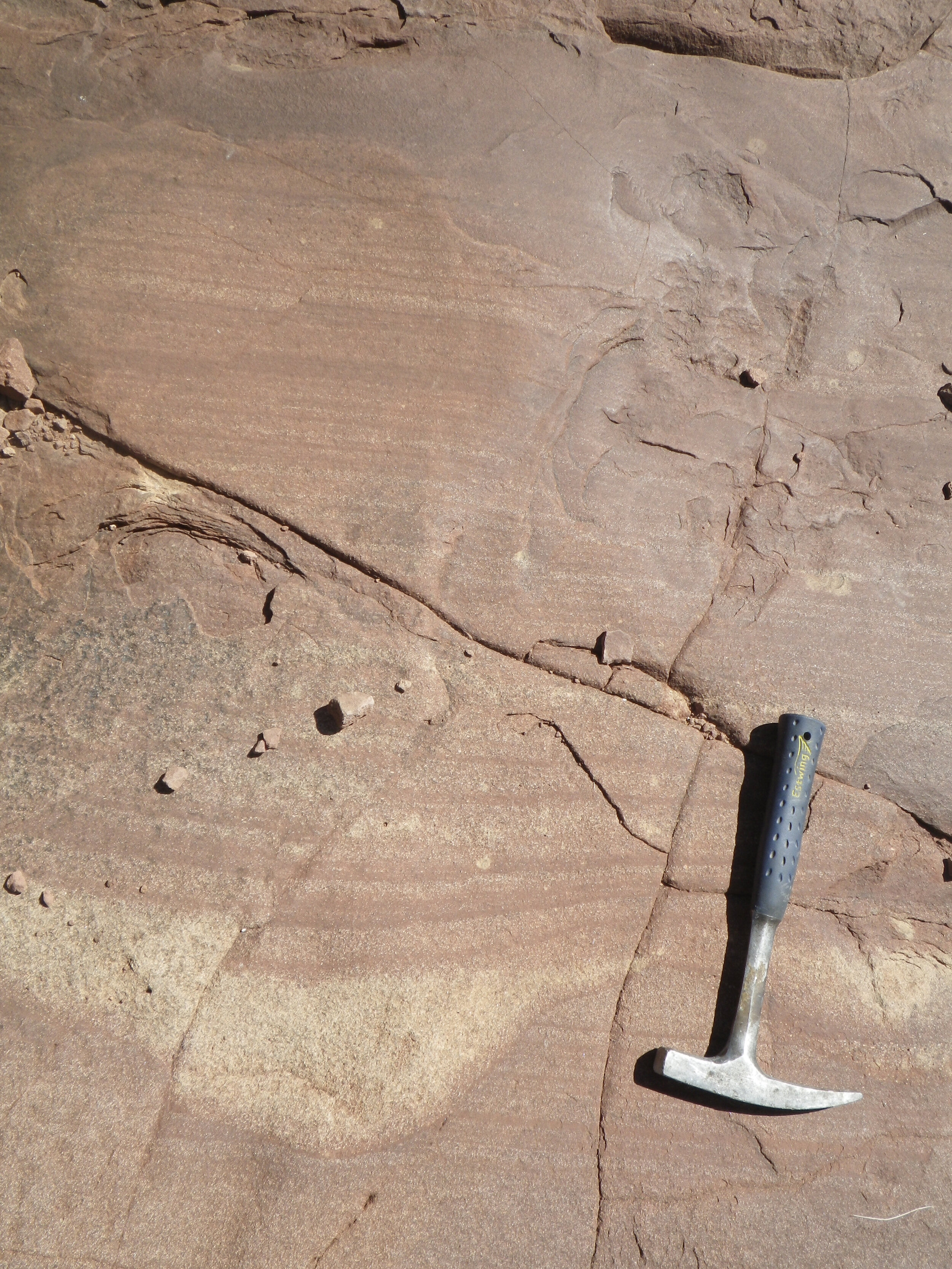

Mount Roe Basalt lava flows, Pear Creek Centrocline; undergraduate field assistant Eric Bolton for scale

Sinclair Group, Namibia

As an undergraduate at Yale, I worked with Professor David Evans and graduate student Joe Panzik on a paleomagnetic study of the Mesoproterozoic Sinclair Group in Namibia, to better understand whether it formed on or was later accreted to the Kalahari craton. For my senior thesis, I produced a new paleomagnetic pole for the Aubures redbeds, the youngest formation in the succession, which suggested that the Sinclair was probably part of the Kalahari at ~1.1 Ga.

Drilling paleomagnetic samples for Aubures conglomerate test with field assistant Jenna Hessert